We are Letícia Goellner and Belén Rodríguez Salvatierra, and in this post, we would like to share our insights on feminist translation practice from our perspective as Latin American women, translators, and researchers in the field of Translation Studies. We will also briefly discuss some ideas specifically related to a collective translation project that we have undertaken in Chile.

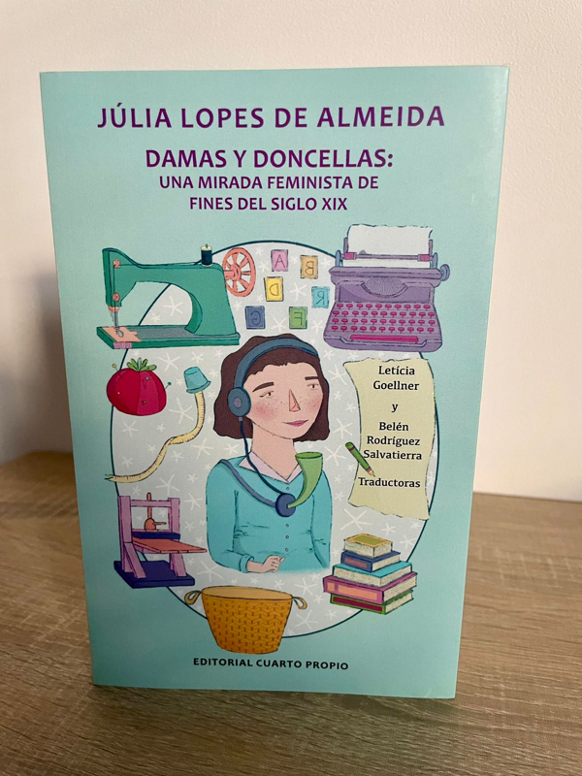

We are referring to our Spanish translation Damas y doncellas: una mirada feminista de fines del siglo XIX (literally in English, Ladies and Maidens: A Feminist Perspective from the Late 19th Century), comprising essays by the Brazilian feminist and abolitionist author Júlia Lopes de Almeida (1862-1934).

Our translation, available here, was launched on 6 September 2024 at the Biblioteca de las Mujeres (Women’s Library), a public institution in Chile committed to promoting literature from a gender perspective. On their website, it is stated that “as the first and only Women’s Library in the country, it holds a collection of books and documents that offer a gender perspective, showcasing feminist works that explore the needs and challenges faced by women, written by women writers or featuring women as protagonists. […] that seeks to raise gender awareness through literature, with the goal of achieving the long-sought equality of rights, responsibilities, and opportunities between men and women in Chile” (emphasis added). The book was released by the publisher Editorial Cuarto Propio (literally, “A Room of One’s Own” Press, in English), which according to Elisa Montesinos is celebrated for its commitment to reviving women authors and supporting emerging voices in local poetry and narrative, as well as for publishing critical essays and cultural and gender studies.

Our book was a collaboration between women in different countries. It contains essays by Almeida which we have translated into Chilean Spanish. The book also features several paratexts that explore the author’s life and work, and examine recent translations into Spanish, placing it within the framework of feminist translation. These paratexts were authored by Dr Ana Cláudia Suriani da Silva (University College London) and Dr Olga Castro (University of Warwick, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), alongside the Mexican literary translator Paula Abramo. Additionally, Damas y doncellas includes illustrations by the Chilean artist María José Testa, which were specially commissioned for the publication, and was proofread by Monserrat Vásquez, a literature graduate from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

The project that led to the publication of Damas y doncellas received support from the Arts and Culture Directorate of the Vice-Rectorate of Research at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, following an application to the institution’s 2023 Creation and Artistic Culture Programme. From the outset of the funding application, the project involved a team composed entirely of women. In total, we are seven women of four different nationalities (translators, essay-writers, an illustrator and a reviewer). We also collaborated with institutions led by women, including Marisol Vera and Paloma Bravo from Editorial Cuarto Propio, as well as Camila Reyes from Biblioteca de las Mujeres. This initiative has several aims, which we will list here. First, to reclaim the figure and work of Júlia Lopes de Almeida within the Latin American literary landscape, where the canon remains predominantly male – and, we might add, Eurocentric or American. Also, to create transnational networks among scholars and translators from various geographical locations, enriching the project with their experience and expertise. And third, to promote the visibility of each team member while questioning and reflecting on the role of women in society, literature, and translation. Therefore, this project has the principles of transnational Feminist Translation Studies, as defined by scholars Olga Castro and María Laura Spoturno in a recent publication, as its guiding thread.

We believe it is important to highlight that the author’s perspective and her feminist ideology should be examined and valued in context, considering the specific environment in which she lived and worked. Our research and translation of her work reveal that she was indeed a woman ahead of her time, but this should not be interpreted solely through the lens of contemporary feminist movements, which have their own distinct contexts and demands. This exercise in empathy, where we immerse ourselves in late 19th-century Brazil through the perspective of a Brazilian writer, allows us to uncover more about our own history – the story of women who bravely navigated a male-dominated world, forging their own paths and striving to establish their names within the elite circles of intellectuals of their time. They addressed pressing issues such as women’s education, femicide, respect for the environment, and the appreciation of Brazilian culture, among others, making meaningful contributions to society. The essays by Almeida which we chose for our edition cover a range of themes, particularly focusing on the promotion of women’s education and autonomy, as well as the friendships and sisterhood among them.

Just as the themes of the essays are diverse, so are the strategies employed in translating them into Chilean Spanish. And yet, they share a common objective: to preserve the author’s style as closely as possible without sacrificing the text’s comprehensibility, while also revealing her feminist ideas. We would like to illustrate this point with the following example.

The author consistently uses the term crianças to refer to children. It is important to note that both criança and crianças in Portuguese, in their singular and plural forms, are epicenes that have a feminine grammatical gender. This contrasts with Spanish, where the most common translation of crianças is niños, a so-called ‘generic’ masculine which not only reflects the male-as-norm principle but also makes women invisible (the feminine niñas could also be possible). To maintain the feminine character of the Portuguese word, we opted for a less conventional translation that retains the original meaning, being also an epicene with feminine grammatical gender: infancias. This represents a grammatical or stylistic adjustment, recently described by Luise von Flotow, as “perhaps the most important contemporary feminist micro-strategy”, that far from hindering the understanding of the translated work, it demonstrates our commitment as translators and our belief in the power of language to create new realities and to perpetuate or question existing ones.

From the conception of Damas y doncellas, we developed several key elements that we consider essential for a project of this nature. These elements distinguish it from other works we have participated in, which either lack such features or do not assign them significant importance. We can categorise these elements into two main groups: those related to the translation project itself and those concerning the translation process. In the first category, we identified the following: the decision to assemble a team composed entirely of women with a critical perspective on our reality, regardless of their explicit feminist affiliations; the promotion of the author’s visibility in Spanish as a way to compensate for the years during which she was forgotten after her death, alongside a renewed appreciation for her work; and the selection of a publisher that aligns with our values and objectives, culminating in the launch of the book at a venue that embodies those same principles. Regarding the elements related to the translation process, we focused on maintaining the author’s style and Brazilian cultural elements, as well as highlighting her feminist ideas. Finally, we cannot overlook the significance of translating a Latin American author within Latin America. While each country has its own specificities and the women who have inhabited them possess their own distinct characteristics (here we refer to intersectionality), we cannot evade the shared colonial heritage of Latin American territories. Thus, engaging with the work of Júlia Lopes de Almeida and undertaking its translation in Chile encompasses a decolonial dimension. Although this aspect may not be examined in detail, it seeks to empower us to reclaim our own voice rather than giving that power to a distant European Other.

Letícia Goellner – Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

Belén Rodríguez Salvatierra -University of Warwick

Illustrations from María José Testa

Reproduced by permission of Editorial Cuarto Propio

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thanks for shening. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/register-person?ref=IHJUI7TF

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://www.binance.com/sk/register?ref=WKAGBF7Y

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://www.binance.info/register?ref=IXBIAFVY

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://accounts.binance.com/en-NG/register-person?ref=YY80CKRN

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?