For the past four years, I have worked with the Stephen Spender Trust to design and deliver creative translation workshops. This February, I had the opportunity to develop one such workshop for the Feminist Translation Network’s symposium at The Queen’s College in Oxford.

The aim of this workshop was to encourage students to think about ideas present in feminist texts, as well as consider feminist translation practices. The poem I chose for my workshop was ‘La forme de ma forêt’ by Laura Vazquez, a poet, novelist, and playwright who won the Prix Goncourt for poetry in 2023. Her work is typically surreal and sensual, and this poem was no different, being an exploration of a woman’s body using animal and forest imagery.

The structure of my workshop followed the Stephen Spender Trust model for creative translation: Decode, Translate, Create. This process offers language learners a scaffolded way to engage with unfamiliar texts, whether they have prior knowledge of the language or not. In this instance, I was working with a group of Year 12 French students, so they were already very familiar with the target language.

Ordinarily, workshops start with decoding exercises, such as extrapolating central themes from a text’s title or an image board and listening to audio recordings to deduce tone and pick out recognisable vocabulary. As this particular workshop was focussed on feminist translation, however, I adapted the activities.

We started by broadly discussing what it means to label a text as ‘feminist’ as well as the themes we might expect a feminist text to explore. Students were then shown book covers of feminist works with their original French titles and their translated English titles. We examined the differences between them and considered whether they had any effect on our expectations for the texts. We also looked at examples of grammatically gendered language in other Laura Vazquez poems, deliberating over how to translate them into English and whether it is important to maintain grammatical genders to convey a feminist message.

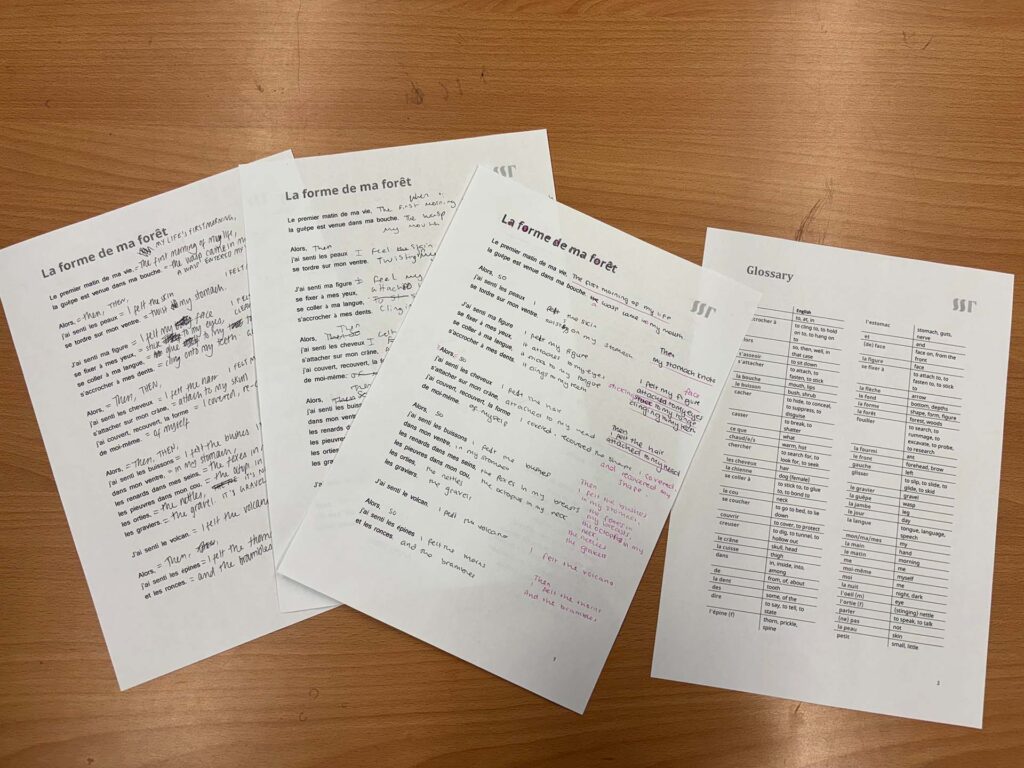

We discussed potential challenges when translating women’s voices, such as the impact of a translator’s gender on their translation of a text. We also reflected on other power dynamics that could be at play, such as race or class. Students were then given the full poem to translate and tasked with creating a literal translation before polishing it to sound more poetic, whether through syntactical or artistic choices.

Afterwards, we examined the main message and themes of the poem, comparing them with our initial expectations for a feminist text. We delved into the vivid depictions of a woman’s body and the natural world, contemplating the relationship between the two. We also reprised our discussion on grammatically gendered language, being that there were several noticeable examples in the text, and shared how we rendered them in English.

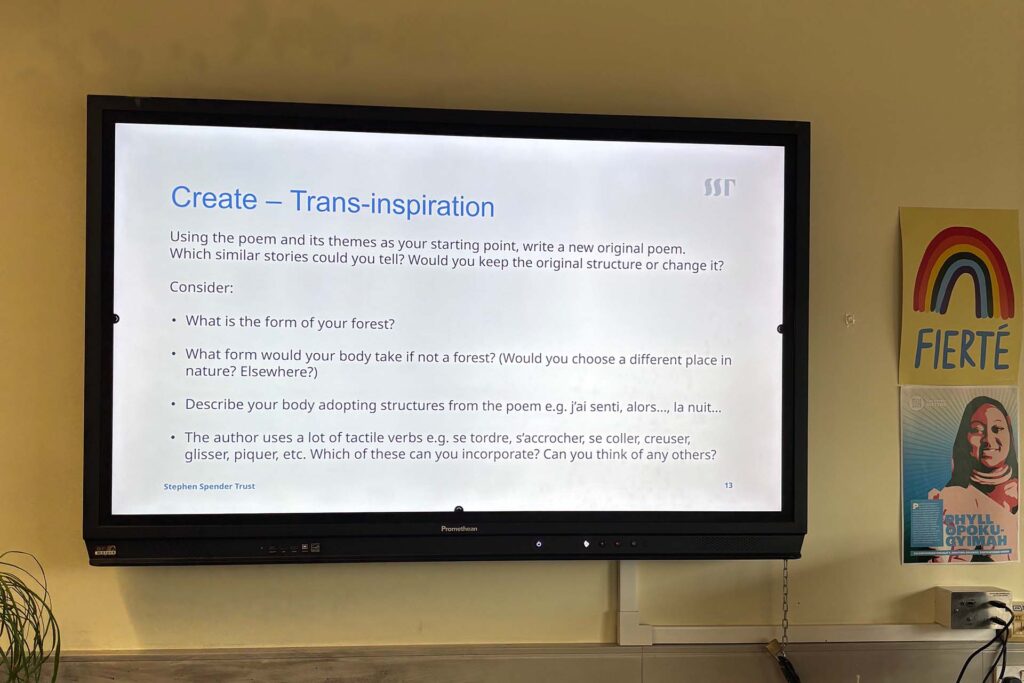

For the latter part of the workshop, students created a piece of writing inspired by the poem. Most wrote entirely in French, repurposing structures used in the text to write about their own bodies in relation to nature. A few students also chose to explore popular feminist motifs, such as the moon and the sea.

All in all, this workshop offered students a valuable opportunity to engage with feminist texts through activities that aren’t typically part of the school curriculum. During group discussions, students were also encouraged to think more critically about how to effectively and ethically interpret women’s voices and perspectives.

Hopefully, the students all enjoyed themselves and will build upon what they learnt to develop their own feminist translation practice in the future!

Sophie Lau

Writer; Translator; Stephen Spender Trust Associate