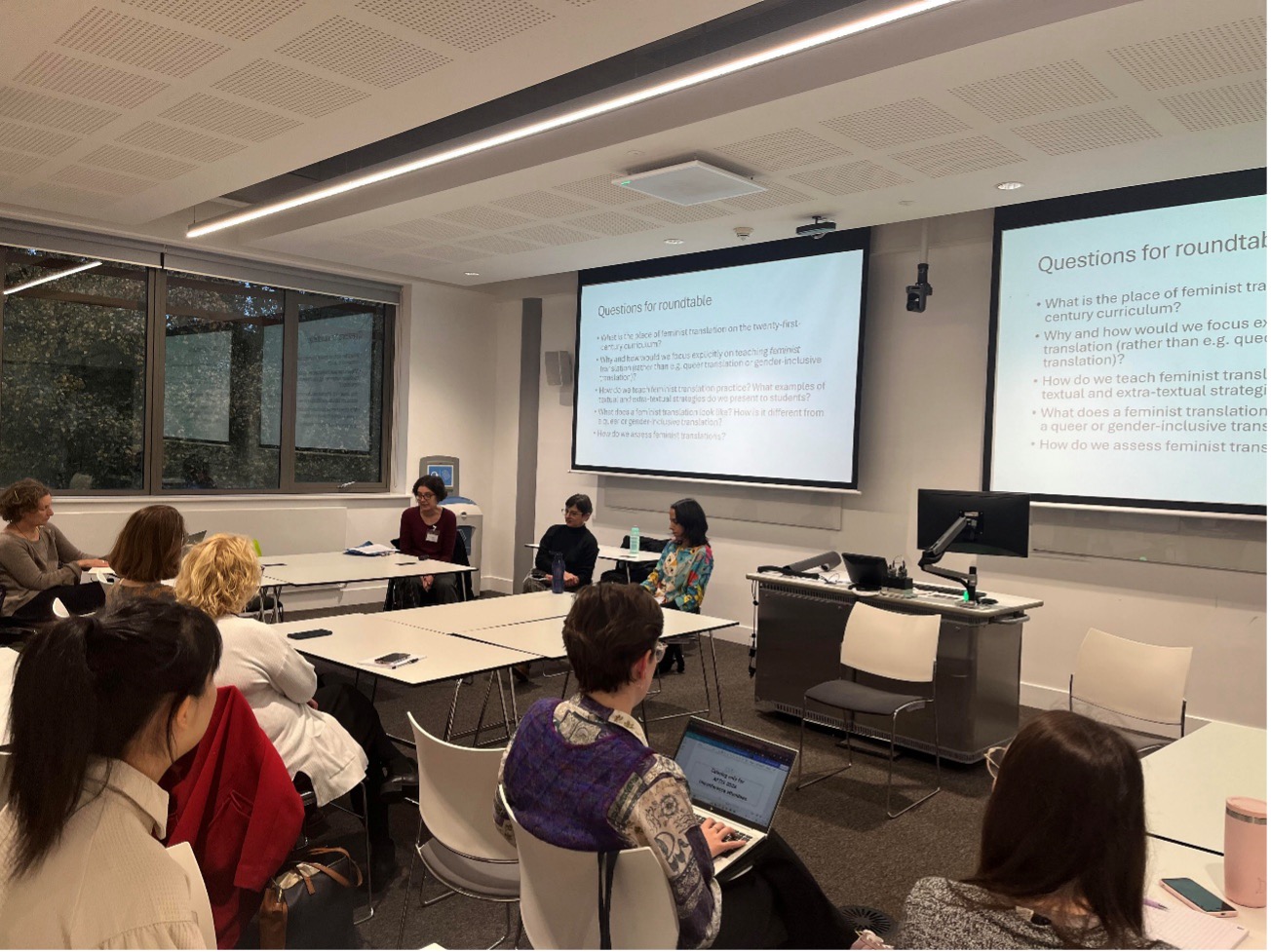

On 7 November 2024, Dr Gabriela Saldanha (University of Oslo), Dr Olga Castro (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona/University of Warwick) and Dr Hilary Brown (University of Birmingham) ran a Hot Topic roundtable discussion entitled “Teaching Feminist Translation” at the 2024 APTIS (Association of Programmes in Translation and Interpreting Studies, UK and Ireland) Unconference, hosted by the University of Warwick.

The aim was to ask questions about the place of feminist translation practice on the twenty-first-century university curriculum. In Translation Studies, the practice of feminist translation is still often associated with the ‘Canadian school’ which emerged in the 1970s-1980s – a group of academics and translators who experimented with rendering avant-garde Quebecois feminist writing in French into English, in ways which drew attention to ‘feminine’ elements. But gender and queer theory have come a long way since then. Key questions for the roundtable included: how is feminist translation practice taught in the 2020s and what examples of textual and extra-textual strategies are presented to students? What does a feminist translation look like and how is it different from a gender-inclusive or queer translation? How are feminist translations assessed? During this insightful discussion, the presenters shared their approaches to teaching and assessing feminist translation, and the attendees commented on how they address this topic in lectures and seminars.

To begin with, Dr Hilary Brown set out some of the challenges in teaching ‘feminist’ translation when there is no longer any agreement about what ‘feminism’ might mean or what ‘feminist’ translation might look like. She introduces students to feminist translation practices as part of a final-year undergraduate module on ‘Translation Theory and Practice,’ which is assessed by a translation project (for which students choose their own source texts and briefs) and commentary. In this module, students are shown examples of Canadian feminist translation but invariably consider them to be outdated given more recent debates about gender-inclusive language; Dr Brown commented that it was not easy to find examples of contemporary feminist strategies in different language pairs to show them. Moreover, students interested in undertaking creative, ‘feminist’ projects had struggled to devise ‘realistic’ translation briefs – one of the criteria for assessment.

Then, Dr Olga Castro explained what doing a feminist translation means for the purposes of an undergraduate module in Modern Languages, focused on translating Hispanic women writers from Latin America, the Caribbean, Equatorial Guinea and contemporary multilingual Spain. She begins the module by asking students to propose their own definition of ‘feminist translation,’ leading to a collective reflection on how the diversity of perspectives on ‘living a feminist life’ necessarily results in different understandings of ‘doing a feminist translation.’ The term ‘gender-conscious translation’ is then introduced, encouraging students to observe how gender issues and ideologies are materialised in a given source text, to then consider different translation alternatives, and ultimately make conscious choices that produce a translation reflecting a process of feminist meaning-making in translation. To assist them in this task, students are asked to create their own glossary of feminist strategies, drawing inspiration from critical readings of academic articles by translation practitioners and scholars who describe and exemplify their feminist approaches in a diversity of languages.

When it came to assessing feminist translation, in this module students are asked to provide a gender-conscious translation and commentary of a given text, following a particular brief. The assessment criteria focus on solving the gender issues that the source text presents, which could be challenging either because the text had sexist or racist connotations, or because it was inherently feminist and translating it in a dominant way would soften the feminist message or would even lead to misunderstandings. When prioritising solutions, non-dominant gender-conscious ways of translating are expected, and examples from actual assignments were shown. A very important aspect that I learned from this conversation is that, when assessing the translation commentary, justifications for linguistic accuracy were secondary to discussions about the student’s intentions behind the selection of specific techniques to translate a text.

Attending the Hot Topic roundtable “Teaching Feminist Translation” at the 2024 APTIS Unconference was an invaluable opportunity to reflect on what feminist literary translation means in practice in the twenty-first century and consider different approaches to teaching and assessing feminist translation in Higher Education.

Daniel Cabeza-Campillo, University of Warwick