In July 2025 I delivered a workshop on Feminism and Translation as part of the professional programme at the Bristol Translates summer school. I based the workshop on the following question: What is “feminist translation”, and why does it matter? The first half of the session was comprised of an interactive talk which invited the 100+ participants to consider how (and why) we might take a feminist approach to translation both in the choices we make about which books to pitch and in the choices we make while translating. The second half moved to a practical exercise in which we were able to apply our ideas and responses to these questions.

Setting in dialogue quotations from some of my favourite feminist activists with perspectives on translation put forward by a range of contemporary practitioners, I aimed to show areas where my understandings of feminist practice and translation practice align. In particular, I focused on their potential to destabilise harmful power dynamics. I suggested that “invisibility” in translation equates to a pseudo-neutrality that masks the normalisation of gender inequalities as outlined by Caroline Criado Perez in her groundbreaking study of “invisible women”. Translation is a political and ideological act, in which translators remake a text in another language (not simply “carrying it across”, as an etymological definition of translation would indicate), and this is not a neutral process. Translators actively participate in the communication of meaning, and so have the opportunity to do this as a conscious feminist practice. This can range from making feminist choices regarding which texts to translate, to the choices we make while translating that pave the way for feminist readings.

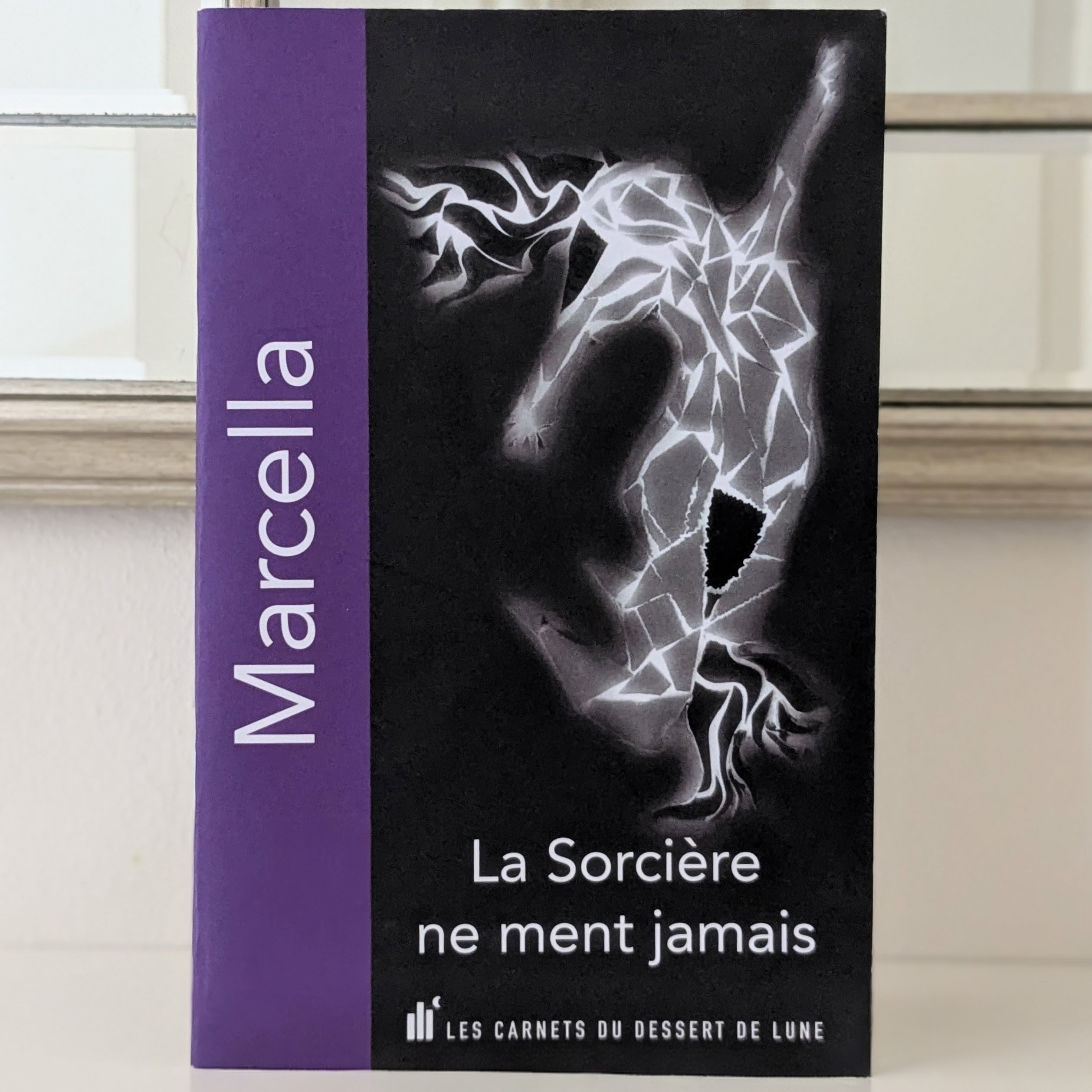

To put this into practice, the second half of the session was dedicated to a series of exercises based on a French poem from Marcella’s recently published collection La Sorcière ne ment jamais(The Witch Never Lies). I selected this poem because its impact is partly visual: until the final stanza, every line begins with the same three-word phrase (“elle a entendu”) and ends with the repetition of another three-word phrase (“elle a obéi”). Participants did not necessarily know what these two fragments meant, but they could see immediately that the phrases (and the repetition of them) were key to the poem’s impact. Next I offered a literal translation of the repeated sections: “she heard” for the line opener and “she obeyed” for the line closer (the lack of capitalisation is another visual feature of the text, disrupting conventional patterns of syntax). Between each “she heard” and “she obeyed” was the kind of maxim that young girls grow up internalising about controlling their appearance, demeanour, interactions and ambitions, augmenting in severity as the poem progresses.

I then provided participants with a literal translation of the poem, and working from this we identified key elements to maintain, focusing on how we would translate the repeated fragments before ending the session with some breakout room discussions in which each group chose a particular line they wanted to work on, based on the literal translation, to make it an engaged feminist translation. From a text the participants had not previously seen – and that, in the first version I showed them, many would not understand – they identified formal properties that had a particular function in the original. Then, from the literal translation they were able to consider what a change of terminology, subject or length would do to the text, and weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of a range of possible translations. Finally, in the choice of which line or lines to translate, we were able to analyse our own internalised language patterns. This encouraged us to consider – and then show through our translations – how the seemingly harmless platitudes we grow up with (“you look much prettier when you smile”) lead to more controlling pronouncements (“your place is in the home”) that can shape the way we relate to the world and have devastating long-term effects.

Helen Vassallo, University of Exeter