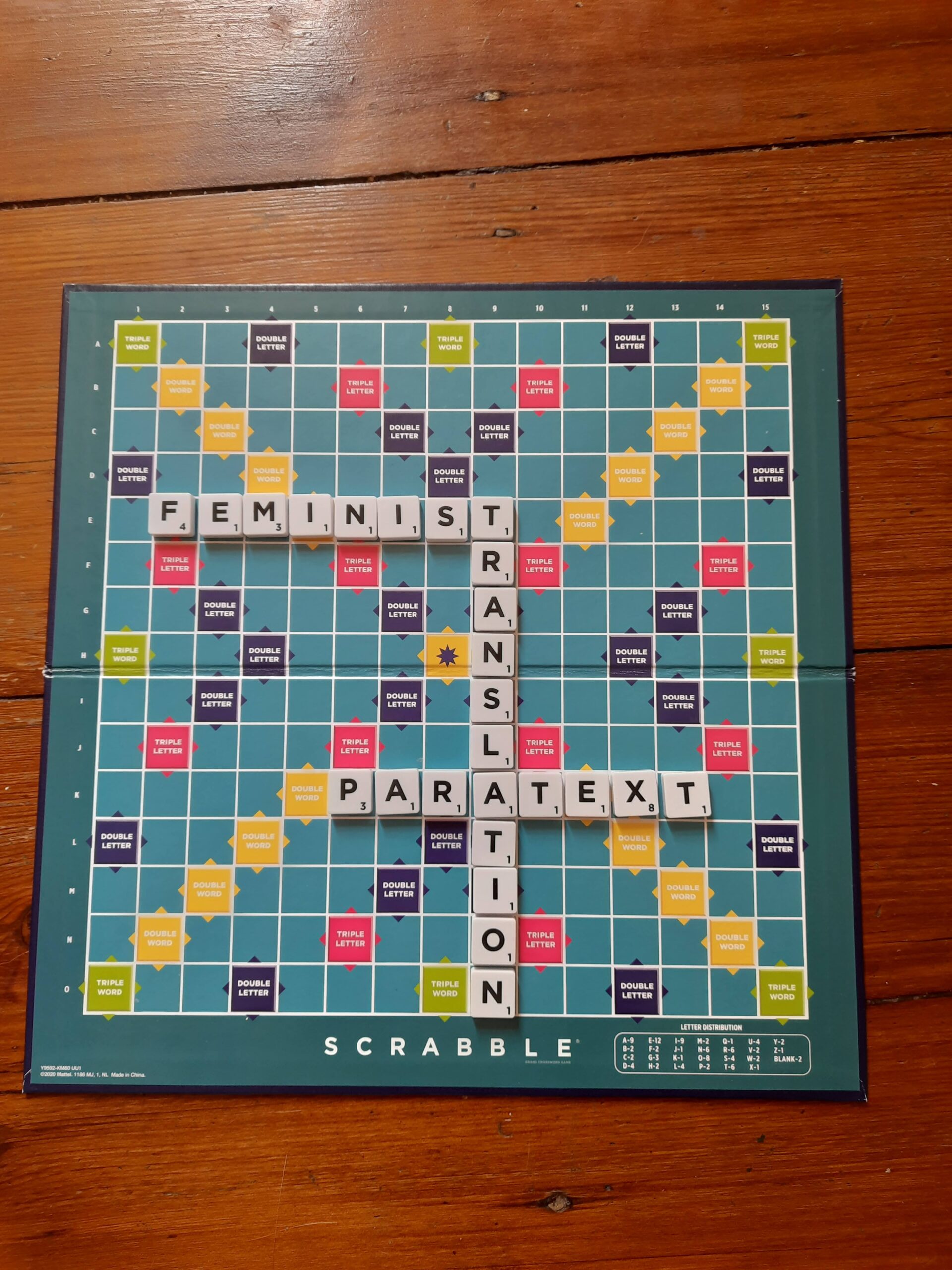

Translators are often invisible to their readers; however, some translators take a paratextual approach to translation. This is a practice that makes the translator visible, by adding footnotes, notes and prefaces to their work. This was a key feature of feminist translations in Canada in the 1970s and 80s and continues to be today. In literary history the active has been seen as masculine, e.g. authorship, and the passive as feminine, e.g. translators. However, in using paratextual techniques translators can make their presence more evident and subsequently active. Therefore, in altering the passive nature of translation one can alter the passive perceptions of the feminine in translation.

For many translations published by commercial publishers, translators are often not credited on the covers of their work and are therefore not visible to their readers. So, there are projects such as the #TranslatorsontheCover movement. This movement is an open letter to publishers urging them to give translators cover credit for their work. Jennifer Croft, who co-authored an open letter to publishers on behalf of translators, wrote a novel that is essentially a pseudo-paratext (The Extinction of Irena Rey). The novel is written about eight fictional translators and is from the perspective of a fictional Spanish translator but ‘translated’ into English by an English translator in the story. The disappearance of Irena Rey is littered with footnotes commenting on supposed translation choices and on the author’s narrative. It features a story told by and about women and in my opinion is a great introduction for anyone interested in the world of feminist paratranslation.

An explicitly feminist translation is Michelle Geoffrion-Vinci’s 2014 translation of Rosalia de Castro’s collection of poems On the Edge of the River Sar: A Feminist Translation. Throughout her work Geoffrion-Vinci uses footnotes to explain her translation choices, which often have intentionally feminist motivations. In the foreword, Geoffrion-Vinci outlines her aims in translating this work, one being “to foreground the female, feminine and … the feminist”. Geoffrion-Vinci makes her presence known throughout the work by using paratextual techniques such as footnotes and a foreword explaining Castro’s position as a feminist and her own translation choices.

However, to have paratextual elements in a translated work, it is not necessary to express comments on the page directly alongside a translation. For example, in Emily Wilson’s translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey she prefaces each work with a lengthy translator’s note. Wilson discusses both choices in her translation and personal motivations for her work. My impression is that in having the translator’s note as a preface instead of an afterword she places the translator, herself, as a part of the narrative Homer had originally created. Also, these paratextual elements help to make texts more accessible to readers who may not have any background knowledge of the book which is more likely in translation than in other works as the cultural context is often very different. Emily Wilson points out in a 2017 Guardian article titled ‘Found in translation: how women are making the classics their own’ that Classics has often been the domain of “elite white men and their bored sons”. A key feature of feminist practice is creating spaces for women in areas – such as classical translation – that have previously been partly or completely shut off to women. Emily Wilson is the first woman to translate both the Iliad and the Odyssey in full into English which, in my opinion, places this text into the realm of feminist translation.

In ‘Toward a Gender-Conscious Translation’, a recent conversation between Marilyn Booth and Yasmeen Hanoosh, the pair discuss the reading of translated works through the ‘lens’ of the translator. When translators make ‘radical’ changes to the text, they have a responsibility to inform the reader. This is done through paratextual techniques. Without an acknowledgment of the role that the translator has had in the alteration of the text, not only can the author be misrepresented but the reader would remain unaware of the translator’s motivations. That said, Booth prefers afterwords to forewords as they seem less “imposing or directive”, preferring not to provide “explicit framing”. Those who adopt paratextual techniques of feminist translation use their presence within their work not only to be respectful of the author but to make the reader aware of the feminist context in which the piece was translated.

One of the main goals of the Feminist Translation Network is to create a space in which to discuss feminist translation. By using paratextual techniques, feminist translators make their work more visible which creates a space for further discussion on the topic of feminist translation.

Eleanor Fillingham, University of Birmingham